Portraits in Silver: A New Chapter in My Work

For over two decades, my work has centred on the landscape—its drama, subtlety, and the stories held in light and stone. It’s a practice rooted in time and patience. Recently, I’ve added a new—but very old—thread to my photographic practice: portraiture made using the wet plate collodion process, a technique first introduced in the 1850s. You’ll now find me in the Kinsale gallery not just surrounded by prints of remote coastlines and brooding mountains, but also quietly pouring chemistry onto metal plates in preparation for a portrait.

So why this shift? And why now?

The answer lies in the same values that have always guided my landscape work: permanence, intention, and beauty grounded in craftsmanship.

Wet plate collodion photography demands all of these—and gives them back in spades. The portraits it produces are rich in tone and character, with a depth and stillness that’s impossible to replicate with modern tools. The process is slow, tactile, and often unpredictable. Each plate is handmade, from coating the surface with collodion to sensitizing it in silver nitrate, exposing it while still wet, and developing it immediately afterwards. It must all be done within a narrow window of time, typically around ten minutes. There is no automation. No second chances.

What this means in practice is that each portrait is truly one of a kind. There’s no negative, no digital file, no ‘undo’ button. The final image—fixed in silver on a sheet of metal—is the only one in existence.

But perhaps the most powerful part of the process is the sense of presence it invites. Sitting for a portrait is not something we do often in our modern lives. We’re used to snapshots, quick poses, and the ability to discard anything that doesn’t meet our immediate expectations. But in the collodion studio, everything slows.

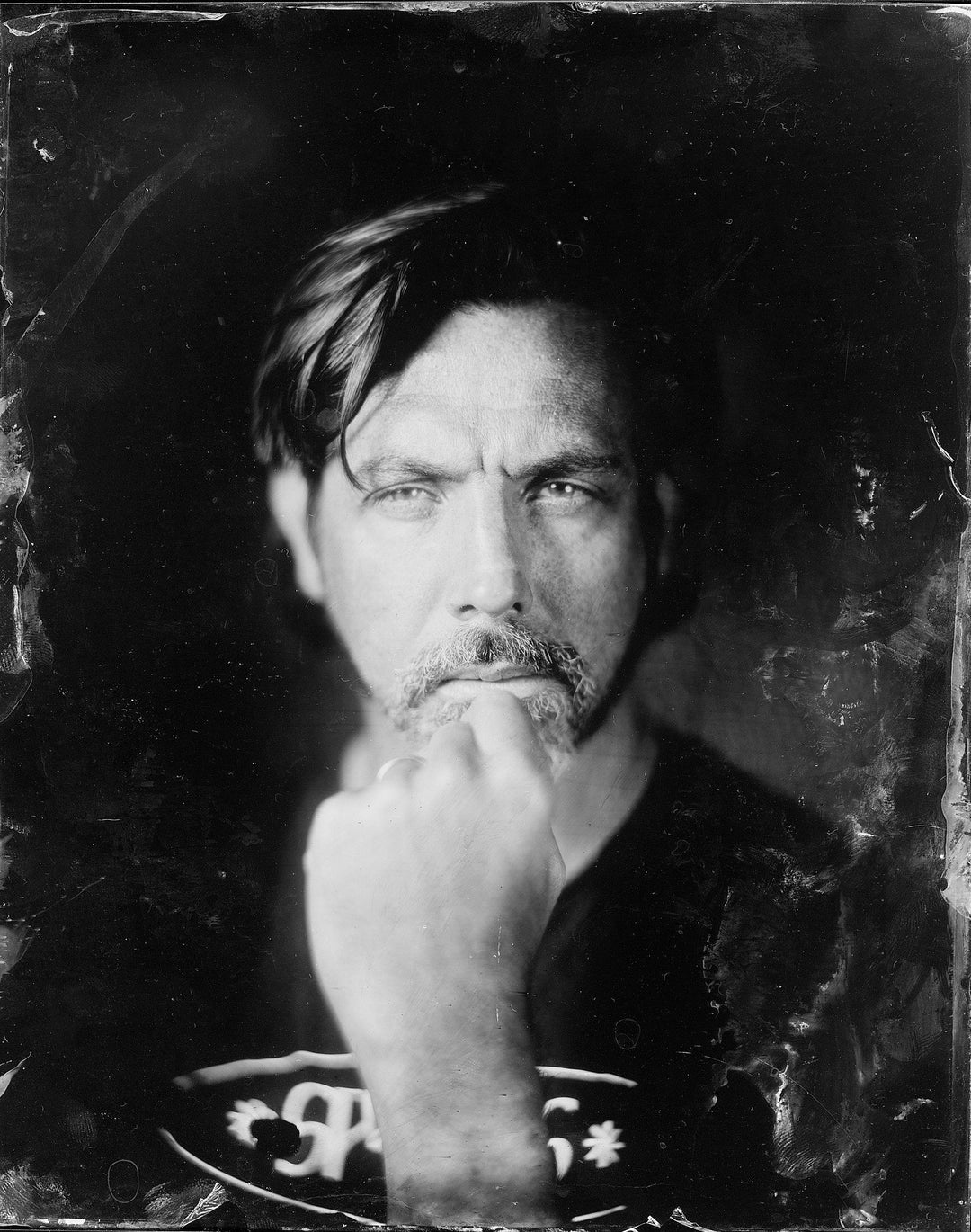

The sitter must be still. The exposure might last several seconds. The camera doesn’t flatter, nor does it judge. It simply sees—with incredible clarity—and records. What emerges is something deeply honest, and often very moving. There’s an intimacy to these portraits, a weight, a sense of time arrested.

And there’s permanence, too. These are objects built to last. Properly cared for, a tintype will outlive its subject by generations. It’s a photograph you can hold, display, and pass down. A family heirloom from the moment it’s made.

For those familiar with my landscape work, you’ll recognise the same commitment to craft in these portraits.

The same reverence for process. And the same attention to light and form. Where a long exposure might reveal the movement of clouds across a ridge, here it reveals the quiet concentration in a subject’s gaze. It’s not a replacement for the landscape work—it’s an extension of it. A new direction, but guided by the same compass.

If you’ve ever been curious about how photographs were made in the early days—or if you’re drawn to the idea of having a portrait made by hand, from start to finish—I’d be delighted to welcome you to the gallery in Kinsale. The sessions are personal, memorable, and often surprising. You’ll not only receive a unique image on metal, but also the experience of watching it come to life.

Click here to learn more or book a session—or simply call in and have a look. There’s always something on the go in the darkroom.

Thanks to Patrick Donald for the photographs of me in action!

Leave a comment